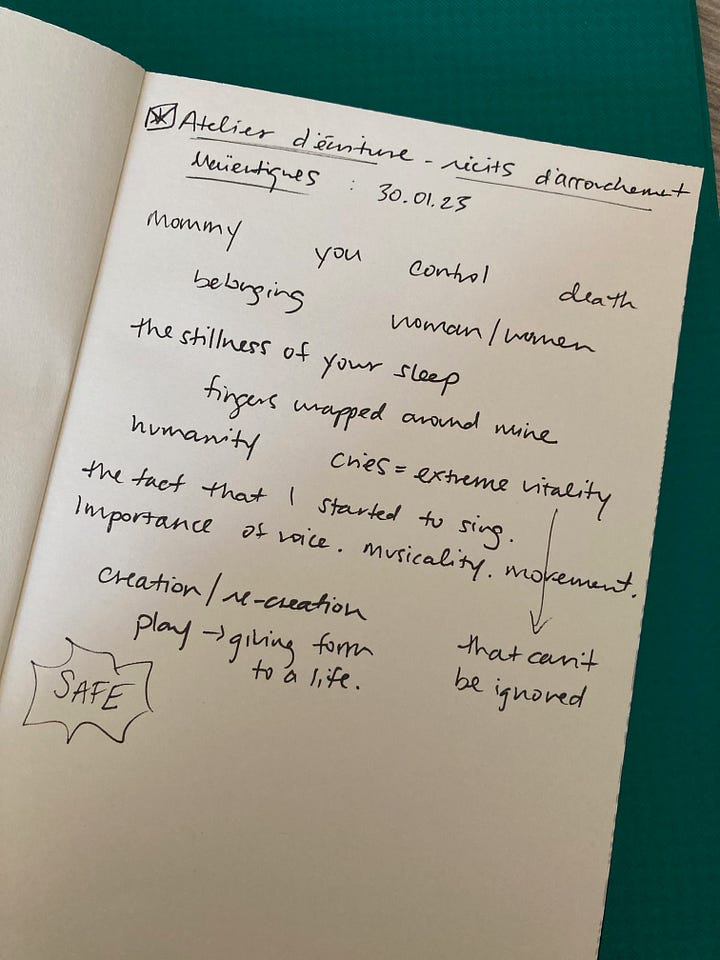

Between January and June of 2023, I partook in a weekly writing workshop held Monday nights in the basement of the university where I work. The theme was “birthing stories” or “récits/maïeutiques”, “maieutics” being a term chosen for its dual definition, as it refers both to midwifery (l’art de faire accoucher) and, in Socratic philosophy, to the art of leading your interlocutor to discover or formulate the truths held inside him or herself.

The workshop was organized by two researchers in linguistics whose scientific objective was to document how women, or parents rather, put their stories of childbirth into words. There would be consent forms to sign, and interviews to be given. Some sessions would be recorded or filmed. The research would be published. The idea is that the study of our stories, our creations built out of the experience of procreation, would allow for better understanding of how the world welcomes our words, alongside our children.

The 10 participants, eight women and two men, all agree that these are essential issues for today’s society. We feel we are helping give visibility to an experience often shrouded in taboo, then laced, at worst, with Instagrammability, and at best, with motherly amnesia (the sequel to baby brain). We hope to be contributing to a collective discussion on pregnancy and birth, and to be shifting the politics surrounding its management.

At the start of the first session, we introduce ourselves: our professions, what has brought us here and maybe something about our offspring. I am Amanda. I am 37. I am from Columbus, Ohio in the United States and I’ve lived in France for 16 years. I am a professor here at the Sorbonne Nouvelle in English and Translation studies and my child is five. I experienced trauma while giving birth and I’d like to see if writing about it might help me work through it.

I say this knowing that the trauma in question resides less in the skin of the day I gave birth than in what’s raveled in the fleshy layers beneath it. More than writing about birth, I am looking for a benevolent space where I am allowed, or even expected, to be vulnerable. Where I can unravel. Like Kafka writes in his famous letter to his father, I seek a place to bemoan what I could not “bemoan upon other breasts.” What the fear of falling on deaf ears had consigned to silence or relegated to the pages of my precious notebooks, to be burned before reading.

Somehow, five years after putting a person out there, letting my writing see the light (dar a luz is the Spanish language expression for giving birth) seems a little less intimidating. It seems necessary even. And the mix of specified scientific objectives (“les enjeux scientifiques de la recherche”) and the mandatory empathy surrounding the theme of the workshop make it feel safe. I wonder if I’ve finally reached that moment when writing, actually writing to be read, has imposed itself and become unavoidable.

At the beginning of the first session though, I’m not convinced that this is the right strategy, neither for producing writing, nor for dealing with my trauma. I confess that maternity is not of great interest to me now, and that I’m not sure I’m in the right place. Some of the participants bring their babies with them to the workshop. I cannot fathom allowing such intrusion into these two hours I’m taking for me, and I do not want to be around babies. I am struggling to conjugate womanhood with motherhood, and am seeking, more than anything, to get a better sense of what it means to be a person. To have a body, to have a mind, to have a voice.

I crave legroom. The room of my own I feel I’ve been denied, without it actually being anyone’s fault. I want to better occupy the lot I’ve been given on this planet and to learn to share it in the most meaningful ways possible.

As we participants smile appropriately, taking in the introductory blurbs we’ve each quickly concocted, we learn that we’ve all to come here to fix something. In our heads, in our bellies, in our homes, or in the transit between head, heart and hand. We have come to document, or to re-write, or to turn the page, and as the weeks go by, we’re all given a chance to cry. “Liberez mon vagin” reads the sticker on the back of the workshop leader’s MacBook Air. There is maybe some of that too.

A woman who carries her baby on her chest writes her first bits of text in her native Hungarian. Since the workshop is being held in French and no one else speaks Hungarian, when it’s her turn to read, we listen with a different attention. What I’ve advocated for in some academic articles (reading beyond the duality of the sign, listening with the body, gleaning meaning through pure emotion) rings true as her voice struggles to break through the air, ripe with our desire to perceive despite the language barrier. Her muscular figure stands rigid. And as her mouth searches for the first word, the baby wrinkles his forehead and lets out a shriek, pure voice, reddening his mother’s cheeks and setting her body into a bounce like the one we all found ourselves doing in those early days.

In the shrillness of his cry, I feel the weight of pure expression and remember Ryoko Sekiguchi’s essay La Voix sombre. Voice is immediate. It touches our eardrums and disappears. The grain of the voice is the body of the voice itself, its members. This is what makes it so difficult, or even impossible, to describe, writes Sekiguchi. In the trembling silence this woman has placed between us, and in the language that remains on the cusp of her lips, release registers only in the form of her baby’s voice. I wonder then, what parts of her remain to break through and can maybe only do so on the page, in her second or third language. A veiling I’m all too familiar with and that I decide, at that moment, to work to thin.

The workshop leader talks of the idea that prosody in the mother’s voice serves as the link between worlds. She means between intra- and extra-uterine worlds, but I think of its anthropological role as well. Entering humanity implies adopting rhythms, conforming to the cultural, and/or distinguishing by burrowing tunnels to escape domination. I have spent the past eight years, since the start of my PhD, studying this phenomenon in literary works and realizing that this is, so far, the question of my life. As the contemporary philosopher Marc Crépon writes, building on Derrida:

“Hors cet idiome singulier [celui que je parle], il n’y a place que pour un sentiment d’exil. Mais cet idiome lui-même (qui n’est pas la langue française) désigne peut-être aussi un autre exil - un exil de la langue dans la langue, un exil de celui qui parle, dans ‘sa langue maternelle’, à l’intérieur de sa propre langue, une autre langue qui n’est pourtant pas une langue étrangère. Quelle langue alors est la sienne ? Qu’est-ce qu'il ‘possède’ au juste ? Où est-il chez lui ? Quelle est sa demeure?”

I recall the instinct to sing in those first few days of my child’s life and how the songs that come to mind are the ones my mother sang to me. Songs I don’t even particularly like. “You are my sunshine, my only sunshine…” Singing, an explicit combination of voice and rhythm, is connection. Voice, though it comes from deep within, is what lifts us out of ourselves. What bridges past and present, self and other, including the other within the self. Crying out, in one’s own voice, own language and own rhythms, brings ecstasy, transport, changes in form.

After years of living abroad, speaking as an other, à côté de moi-même, embodying with difficulty the words I write, no matter the language, the “birthing stories” workshop provided me, above all, with a birth place. Starting blocks to help me navigate the pull of the changes in orbit around me.

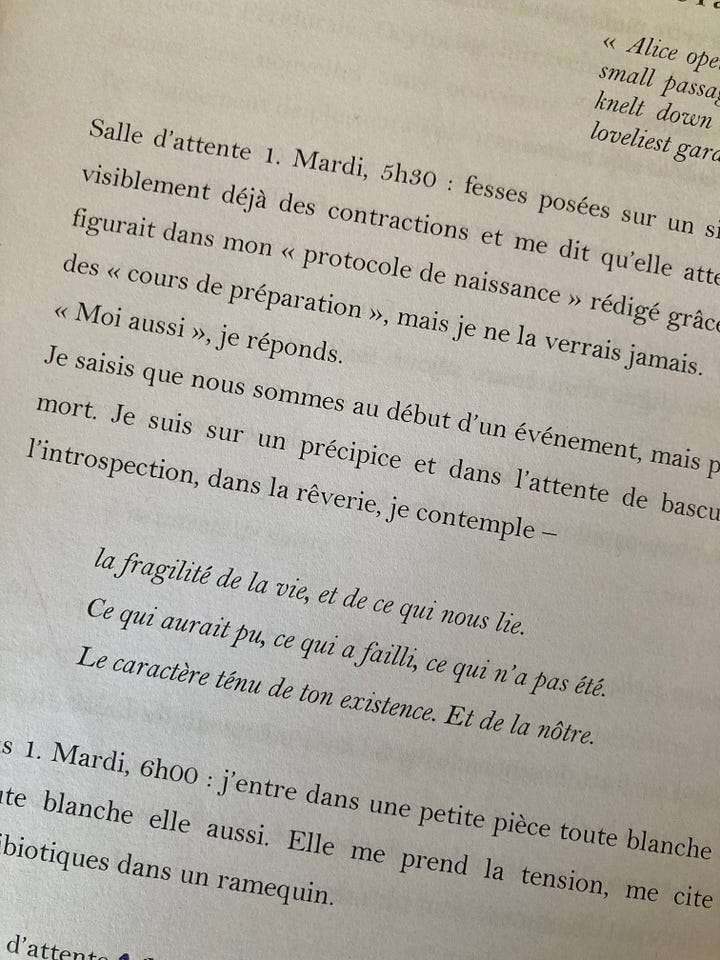

The text I produced by the end of the workshop is surely worth something. But rather than take it as a finality, or publish it here and now, as the story, I’ve decided to frame it as a starting point. Within this space, I will pull on its threads in hopes of weaving something new. This will be a story of trying to tell a story.

Thanks for listening.

"mommy you control death" mmmmmm. can't wait to read the piece if you decide to share one day, but this is brilliant and delicious all in itself.

Thank you for letting me in with this vulnerable brave piece. I ached for the 11yr old girl, shifting through regulated versions of "home" and so much better understand who you are in your trek through life and striving for the solid foundation of home we all crave. I see the driftwood plaque hanging in the kitchen How poignant. Sad irony. I wonder if taylor and jarrett had similar feelings of displacement never really being settled. I reflect on my need to try and provide for them a sense of home which means, "A soft place to land" I think back to the confused 7 yr old Beth not understanding why my home was being shattered with betrayal, hurt, and then aggressive bitterness displayed by Dad. I am thankful that by the time i returned "home" to Ohio in 1987 he had softened and became a gentle support for me, and a friend. Broken, yes, as many of us are, and who left this place before he could work out those demons inside. But i know he is free now and provides me his signs when im back on the right path. I love the collection of stones analogy to build a foundation that was lacking, but which we all deserve. Also, the timelessness they possess. So much to share. We have some differences in our interpretations of a few things, but i respect and appreciate you allowing me to better understand who you are. I will always love my Amanda Panda, but i adore the woman you are becoming as you continue to seek and receive. Some say life isnt about finding the answers but living in the questions. I love the human ability to self examine and metamorphize as we do. Dictionary term Self actualization. Becoming... I could go on ad nauseum with philosophic quips, but ill leave it as this, until we meet/share again, keep collecting, and keep your socks up sister! Did i mention i love you tremendously!